Being a payroll person, logic and patterns are part of my day to day. So, when patterns begin to appear in other ways, I don’t ignore them. Recently I‘ve been asked (on multiple occasions) to explain how tax deductions have been calculated, and this becomes a very interesting challenge for me when the person asking the question has me in their world so they don’t have to get into the nitty-gritty of payroll, but want to understand their tax deduction. After doing this on multiple occasions, I thought it was time for a blog.

How Is Tax Calculated: Tax Codes

The first thing to do is to take a look at your tax code. For 2022-23, it’s highly likely you’ll have a tax code of 1257L. If you have a code with a higher or lower number, but ending in an L, keep reading. If you have a different letter, we’ll come to you in the next blog.

Once we’ve established you have a tax code that ends with an L, there’s a further check to make. There may be another indicator after your tax code. It may say M1, or W1, M1/W1, or even possibly X. If you have any of these, lets walk through how your tax is calculated.

But before we dive in, I want to explain some terms I’ll be using throughout the blog.

- Gross Pay – this is your pay before tax, national insurance or pension is deducted, and is made up of all the pay you receive. So gross pay can be salary plus bonuses, commission, overtime, or any other payments. If your employer refunds expenses to you, these aren’t part of your gross pay. Gross pay is the amount that your tax, national insurance, and pension contributions are calculated on.

- Net Pay – this is the amount that remains after tax and national insurance have been deducted. You may also find that your pension contribution is deducted from your gross pay before tax and national insurance is deducted, and this is dependent on the type of pension scheme you’re in.

- Take Home Pay – no explanation needed here! However, you may find that this is different to your net pay, as your pension contribution may be taken from your pay after tax and national insurance has been deducted. If your pension scheme is with Nest, this applies to you.

- Tax-free Pay – the amount of money you are allowed to earn without paying tax, which is indicated by your tax code

- Year to Date – the total amount of earnings, or total tax deducted from your pay since the start of the financial year. This term can also be used in relation to national insurance or pension contributions.

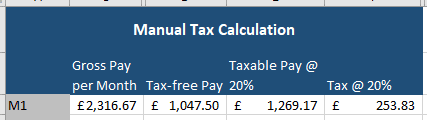

So, back to having another indicator after your tax code, if you have M1 or one of the other indicators mentioned above, your tax is processed under what is called the Week1/Month 1 basis. This is a reference to how tax is calculated in the first month of the tax year. The first thing we need to do to work out tax this way is to look at the start of your tax code again. Let’s use 1257L as the example. To begin to calculate tax using the Week1/Month 1 basis, take the tax code of 1257L, drop the L off, add a zero and turn it into a money value. So 1257L becomes £12,570.00. This is your tax-free pay, the amount of money you can earn in a year without paying tax. The UK tax system spreads this evenly across the 12 months of the year, so we divide your £12,570.00 by 12. This gives us £1,047.50. This is the amount of money you can earn gross before you start paying tax in a month. After that, tax is calculated on every pound at 20%.

Scenario Example Of How Tax Is Calculated

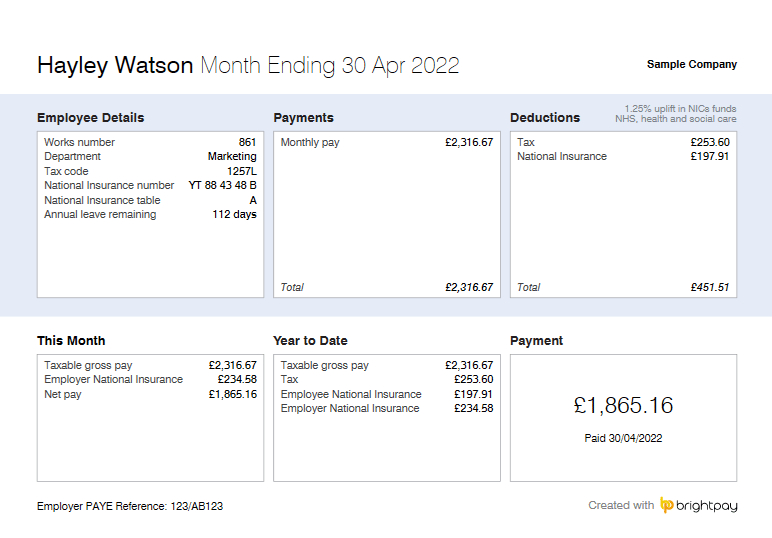

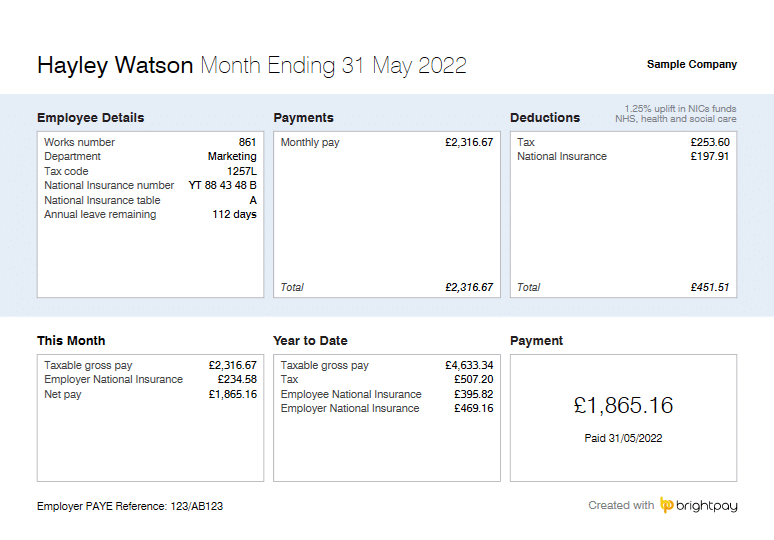

So, let’s create an example of that. Taking annual earnings of £27,800.00 per year gives a monthly gross of £2,316.67. We already know that with a tax code of 1257L you can earn £1,047.50 per month before paying tax, so deducting that from the monthly gross leaves £1,269.17. We then need to calculate 20% tax on that amount, which is £253.83. Going back to the monthly gross of £2,316.67, we deduct tax of £253.83.

When you do these calculations yourself, you’ll notice your pennies out, if you’re comparing them to a payslip as you see above. HMRC are naturally to blame here 😊. Prior to the fantastic payroll software, we have today, cumulative payroll was calculated manually for each person, and tax calculation used books of tables. Suffice to say table method and the ‘actual percentage’ method that we’ve walked though above result in slight differences. Both methods of calculation are allowed. Most software calculates using table method so you may find variances, but if you’re in the ballpark of a £0.40 in a month (or probably less), your calculations can be trusted.

If you are on a W1/M1 tax code, this is how you calculate tax for each month in the year.

Cumulative Tax Calculations

Now this is where it gets interesting, and the explanation gets more detailed. If you haven’t got one, grab a cup of tea (and a biscuit if you’re feeling like you need a snack to sustain you through the next set of calculations) a note pad, pencil, and a calculator.

Welcome to the world of cumulative tax calculations!

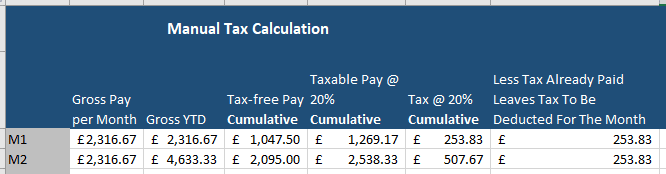

If your tax code doesn’t have the W1M1 or X indicator after the L, your tax is calculated on what is called the cumulative basis. Simply put, your tax isn’t calculated on your earnings in the month, but on your earnings year to date, then the tax due is adjusted to take into account the tax you’re already paid. So, we need to get more detailed about how we calculate this. In April, the first month of the financial year cumulative tax is calculated in exactly the same way as Week1/Month 1 tax. However, once we get to May, this changes. As we’ve already discovered in the W1/M1 calculations, you can earn £1,047.50 per month before paying tax. We’ve already established that this figure comes from being one twelfth of your tax-free pay, so in May (month 2) we can use two twelfths of the tax-free pay in our calculations. Let’s dive right into this.

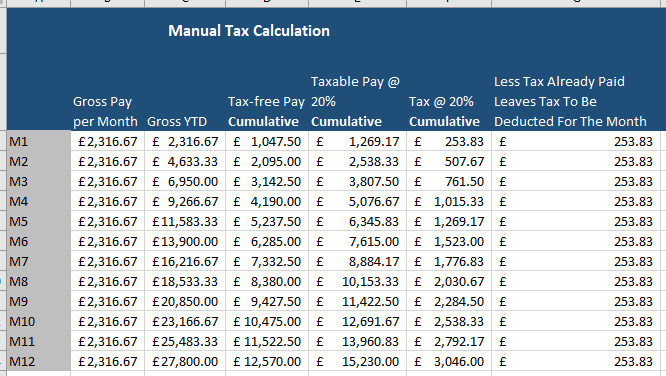

Sticking with our example above, an annual salary of £27,800.00 gives a gross monthly salary of £2,316.67. So having processed payroll for April, your year-to-date gross earnings are £2,316.67, and your year-to-date tax is £253.83.

Jumping forward a month, payroll has been processed for May, and your gross earnings year-to-date become £4,633.33. Next, we look at your tax code of 1257L. We know we spread the tax-free pay evenly throughout the year, so as we’re in month 2 of the financial year, we can use two twelfths of the tax-free pay against 2 months of gross pay. £1,047.50 is the monthly amount of tax-free pay, so 2 months are £2,095.00. Quick calculation at this point, £4,633.33 minus £2,095.00 leaves £2,538.33. Tax is then calculated on this amount at 20%. This produces a tax figure of £507.67.

What I’ve found is at this point, people begin to get nervous. They’ve already paid tax in April of £253.83, and we’ve just calculated a tax figure for May of £507.67 which looks rather large and scary. Bear with me, this is cumulative calculation. What we do here is look at how much tax was paid in April and deduct that from the tax figure we’ve just calculated, and this becomes the tax deduction for May. That calculation is £507.67 minus £253.83. May’s tax becomes £253.83. Instantly more recognisable in comparison to April.

And the year continues on using the same method each month. Year to date earnings less year to date tax free pay leaves the amount of earnings to be taxed. Calculate the tax value and deduct the tax paid year to date, and you have tax for the month.

So there’s cumulative tax, in a nut shell! It does have a further level of complexity when your annual earnings are above the 40% tax bracket, but we’ll leave the fun of that for another blog!

If your tax code isn’t 1257L but still ends with an L, the above method will still work. Simply drop the L, and a zero and do your ‘divide by 12 months’ calculation to get your tax-free pay for the month in April. As we did above, multiply by the month number you’re calculating to work out your cumulative tax-free pay.

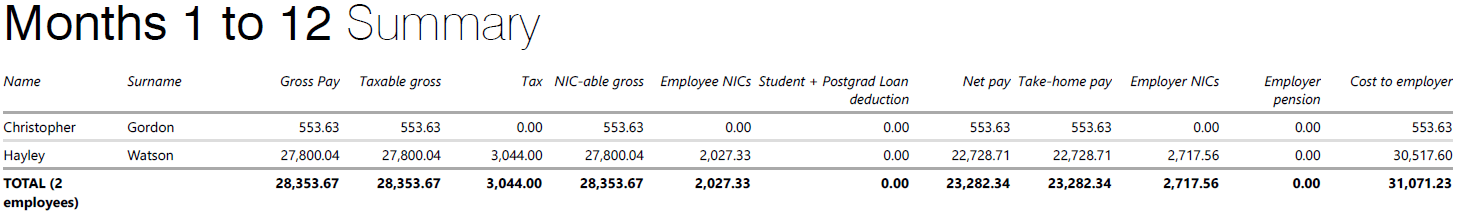

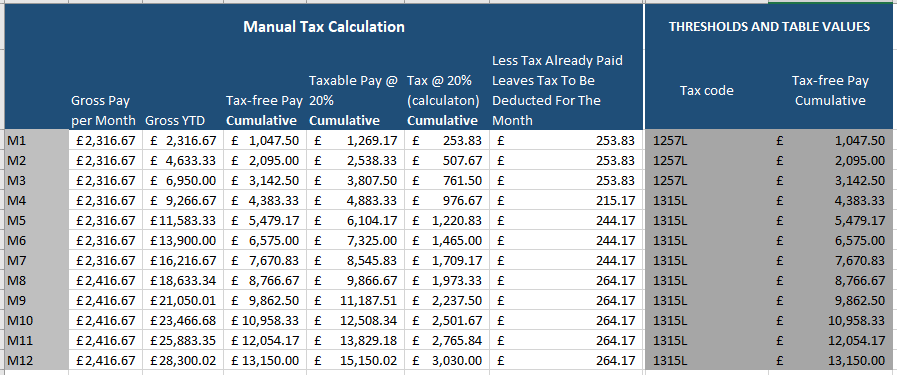

Below you can see how the 1257L tax code works throughout a year. This is a very simple example, as there is no change to monthly pay or the tax code during the year. The process doesn’t change, even if you have a change to your tax code and gross earnings during the tax year, and you can see how that looks on the image further down with a tax code change in July and a salary increase in November.

Tax code change in July and a salary increase in November.

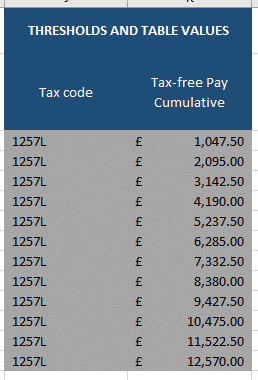

And here is a table that shows how the tax-free pay is spread throughout a full financial year.

Struggling with Payroll?

If you’re managed to get to this point in the blog, thanks for sticking with me. I really hope you’ve found this helpful. But if you’re an employer who is struggling with payroll, and it’s causing you a headache each month, why not give us a call to discover if we can help. Payroll outsourcing is more affordable than you’d imagine and amongst other things, we guarantee a headache-free month end.

Call Nadine in the office on 01384 929020. I look forward to speaking to you.